Slow growth is weighing on world GDP. Can India replicate the magic of Asian Tigers?

May 03, 2023 - Anurag Singh

After witnessing growth spikes of 8%-plus in 2015-16, India is now averaging at 6% or below. While the slowdown is the result of larger forces at play within the global economy, to stand out India must make extraordinary efforts, like China, OECD nations, and Asian tigers have taken in the past. Can India surpass China on the global stage?

Can India attain an over 8% growth rate again? In our previous article, we have had two open questions. The first was about the slowing pace of the Indian economy. Backed by data, we put forth that the prime phase of near 9% economic growth, witnessed between 2003 and 2008, is unlikely to be repeated anytime soon.

Today’s piece addresses the second and an important question — why is it that that prime phase can’t be repeated?

Meanwhile, most economists also appear to be divided by the camp they belong to or the regime they support. However, getting lost in either of the narratives is missing the big picture.

We all support India’s cause to grow fastest in the world and reach a middle-income nation status. But the task, as we shall see, is much more difficult vis-à-vis the narratives or the rhetoric.

OECD nations as economic leaders: 1960-1985

The analysis has to begin from the 1960s and see how the leading rich economies started to take an early lead. After World War-II, a period of sustained peace arrived, and investments started in infrastructure and industries. Most importantly, people began consuming and spending with more stability around the future of life. The generation is called baby boomers for a reason!

The following two decades saw an average of near 5.25% growth in the world’s GDP. In absolute terms the global economy grew from USD1.5 trillion to USD5 trillion by 1973, and USD10 trillion by 1979.

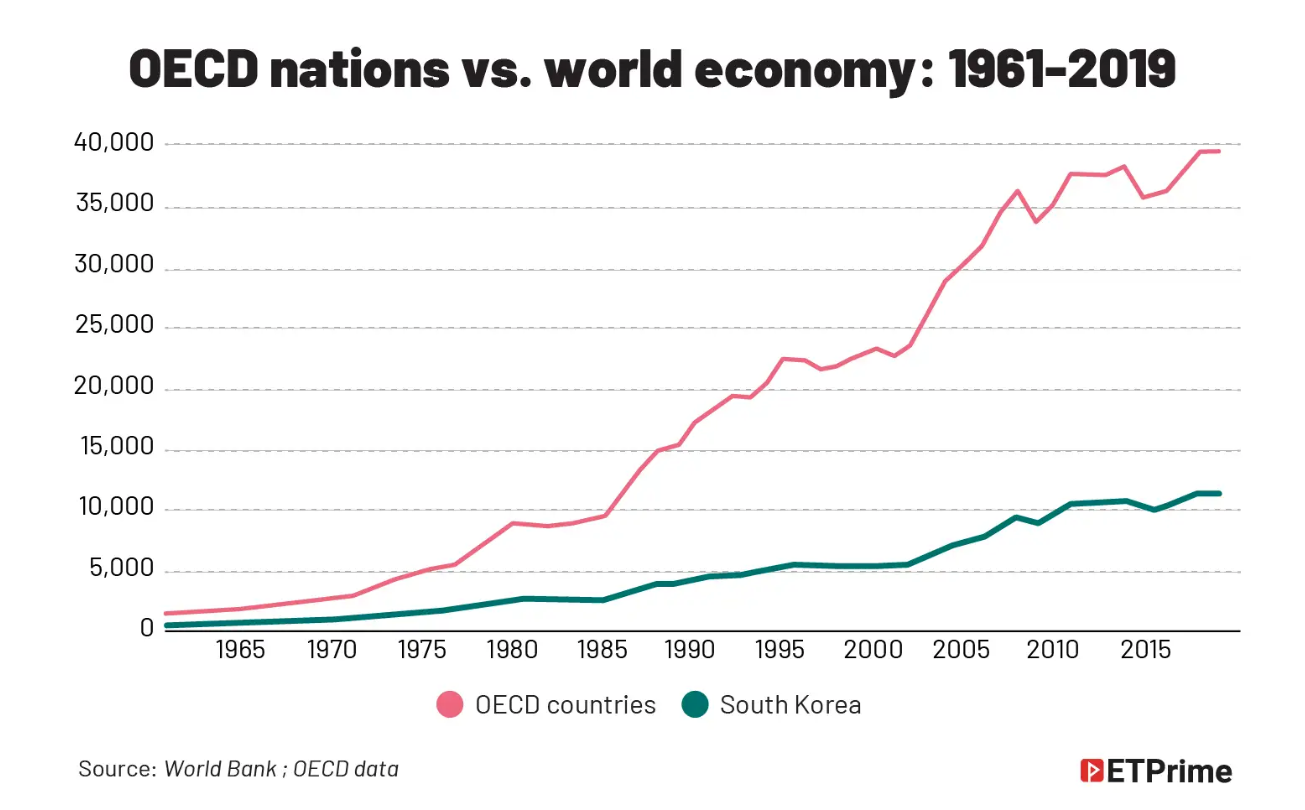

The per-capita growth almost averaged 12% per year between 1971 and 1980. While the world averaged at ~USD2,500 per capita in 1980, most OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations were approaching middle-income levels of USD10,000 per person.

Further significant change was taking place through the productivity improvements. The per-capita GDP of the world, growing at 12% during 1970-1980, indicates how strongly labour efficiency was contributing to the economy. This productivity growth was the major phenomenon propelling the industrialised nations ahead of countries that were largely agrarian economies.

By 1986, the world’s GDP had risen to about USD15 trillion i.e. 10x from 1960 levels. So, who all gained?

Almost 66% — two-third of the growth between 1980 and 1990 was still being contributed by the US, Europe, and Japan. For perspective, India and China together added just 2% to the global growth then. While the West was still going strong, it was the turn of Asian tigers to come to the party.

Asian tigers roar: 1976-2000

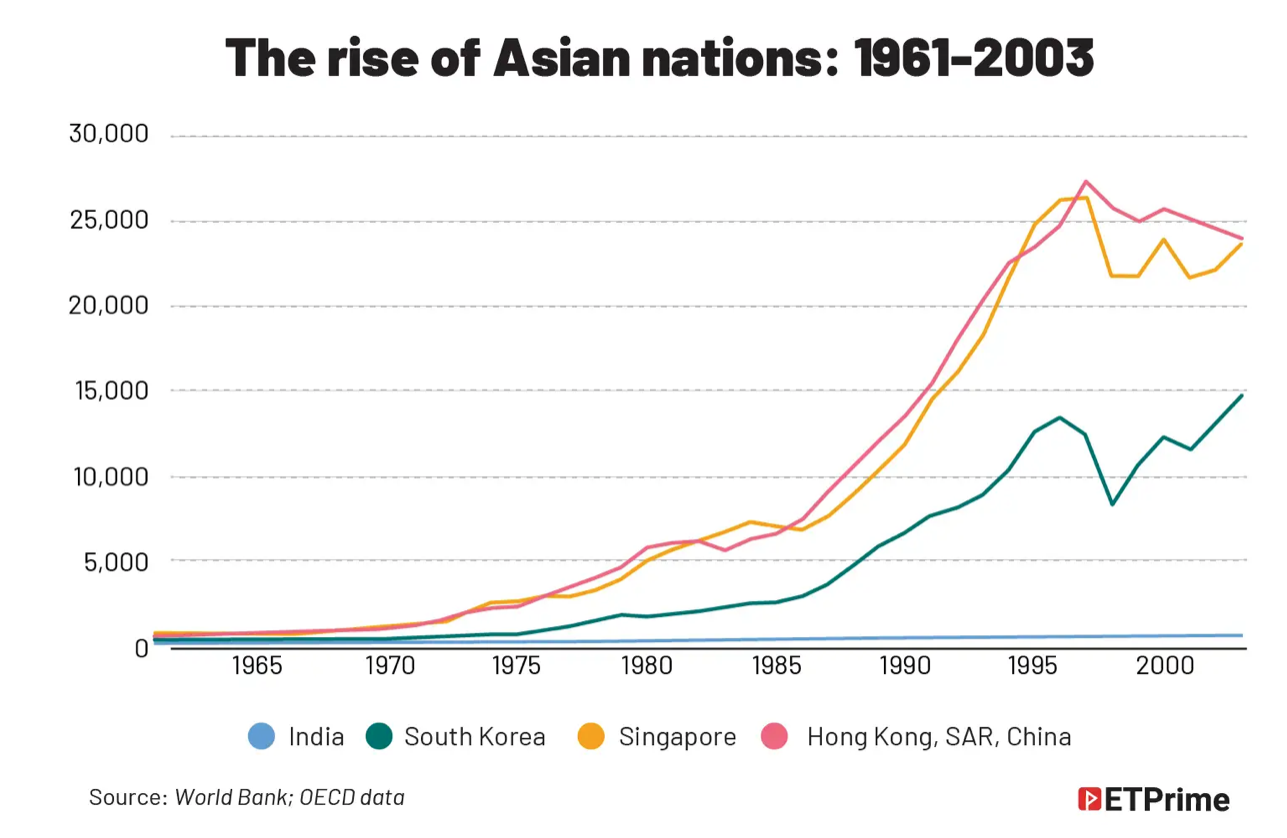

While industrialisation, investment and consumption were the themes for growth amongst OECD nations, there were limitations to this within smaller Asian countries that had limited domestic markets. The solution was to leverage the fourth component of the growth equation — exports. The same was adopted and executed with near perfection by other Asian tigers.

The 1970s and 80s saw the rise of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. They largely followed the Japanese model of low fiscal deficit, flexible exchange rates, low inflation, limited debt, and overall macro stability for a predictable business climate. Above all, they invested in education and human infrastructure for the futuristic development of its workforce.

Overall, the Asian tigers plus Japan contributed ~12% of the global growth during the 1980s — a significant contribution considering their low population base. This catapulted a few more nations to the middle-income status as their per capita GDP spiralled 6x-8x between 1970 and 1990.

As we shall see ahead, sustaining a CAGR of even 7% for 20 years is much more difficult than it appears, especially when a country hits the middle-income zone. The 1990s saw continued dominance of the United States as it alone accounted for 40% of the world economic growth with Japan taking up another 15%. The overall global growth, however, slowed to 3% for the decade as larger economies matured. The world was looking for the next revolution outside the known giants.

The decade of BRICS: 2002 to 2010

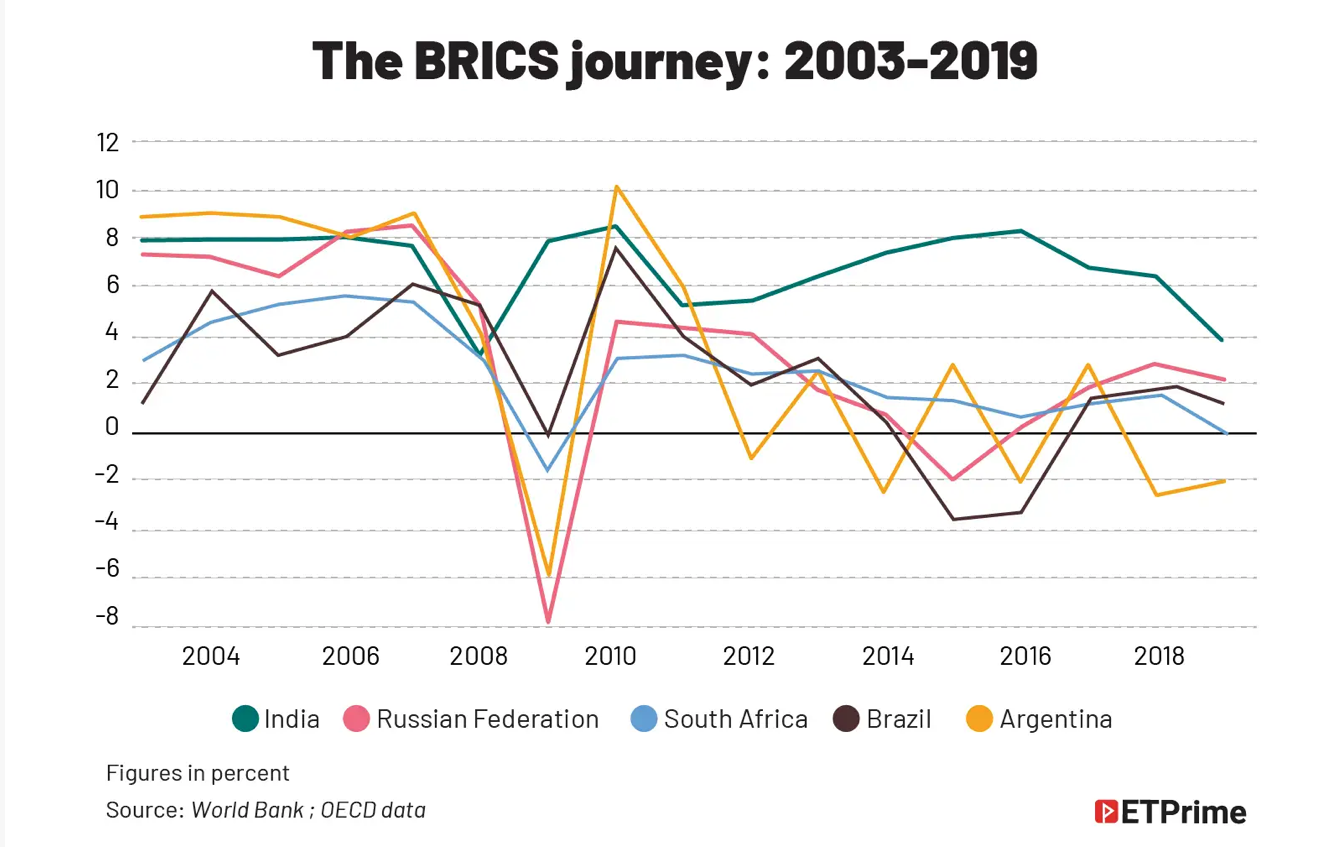

Goldman Sachs coined the term BRICS in early 2000s for the economies that could contribute the most to global growth in future. Given that the Americas, Europe, and Asian tigers had attained maturity, the global economy needed new engines.

China, Argentina, India, and Russia attained above 7% growth starting 2003 and 2004. Brazil grew nearly 6% in 2004, and the promise of BRICS started to look real. It was China, however, that started the real growth trajectory starting at 10% in 2003, 12% in 2006, and 14% in 2007. Despite this, the global growth stayed at just 3% for the entire decade.

After the global financial crisis in 2008, BRICS journey ended abruptly. Brazil, Russia, Argentina, and South Africa were hit hard by the commodity downturn and could almost never recover from that.

From sub-4% to even negative growth became the norm for these economies. We all know the continuous decline thereafter for these economies till date. The graphic below tells the entire story.

The middle-income trap

Did these economies miss the track? Not really. If we examine the per capita GDP, we find that Argentina peaked out at USD14,600 in 2017 and has declined to near USD10,000 now. Brazil spiked to USD13,200 in 2011 and is now hovering at USD7,500 per capita today. Mexico is stagnant at USD10,000 per person level since 2008. Russia’s peak was USD16,000 in 2013, which has now dropped to USD12,000. South Africa could attain USD8,700 by 2011 and has been downhill since then to USD7,000 now.

There is an important lesson here for us. As nations grow to being middle-income countries (USD10,000 per capita and above), they begin to stagnate unless there are institutions and human capital that match the standards of Western economies or select Asian giants. Growth is not an entitlement forever.

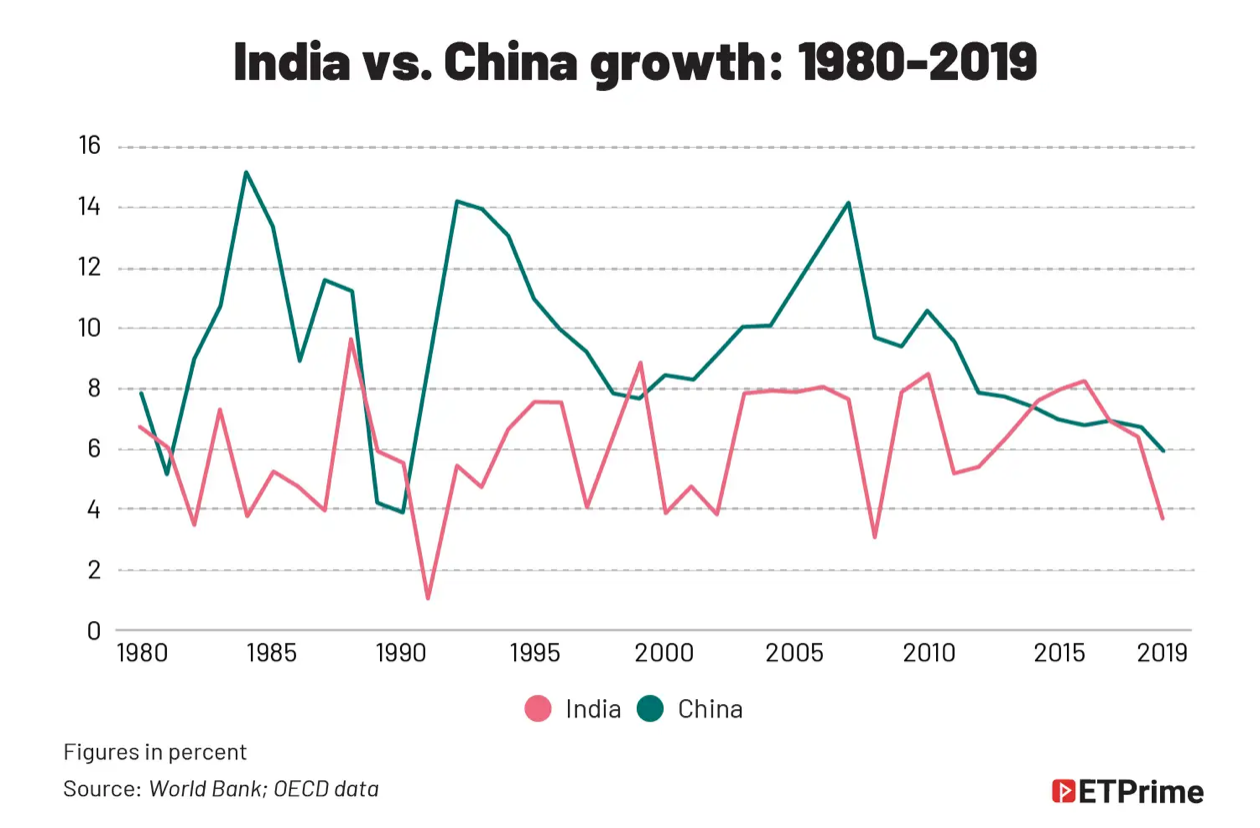

This brings us to India and China, which defied the trend after 2008. China continued to grow around 10% until 2011 and then shifted gears to 7% and later to 6% by 2019. This drop has to be seen in the context of a much larger base and China reaching the critical middle-income bracket at USD12,500 per capita income in 2021. Being a USD15 trillion-plus economy, it would be a superlative achievement if China can still grow at 5% rate.

Meanwhile, India was growing no less. We shrugged off the dust after the global crisis in 2008 and stood back at 8% by 2010. By 2010 though, slow decision making and controversies during the then government hampered the investment climate. India hovered between a 5% to 6% GDP growth rate.

In 2014, the Narendra Modi government took charge and revived the spirit. We had a few good years of around 8% growth till 2016.

But when the world is slowing fast, how could India sustain super-normal growth with incremental efforts? After all, the global growth averaged at mere 2.7% between 2011 and 2021. The projection going forward is sub-2%.

Losing steam or an after-effect of low global growth?

Regardless of growth spikes of 8%-plus in 2015-16, it is now evident that the Indian economy has lost its mojo and seems to be averaging at 6% or below. So, what happened here?

While one set of economists argue that the near double-digit growth between 2002 and 2010 was due to right policies pursued by the Manmohan Singh government, simultaneously pointing that the policies adopted by the Modi government — notably demonetisation and GST implementation — dented India’s growth trajectory to a mid-single digit level. Some other macro economists would quote lack of investment that peaked in 2008 at 35% of GDP and a slowdown in bank lending.

The cause and effect is a matter of debate but it is obvious that if investment drops, bank lending would stagnate too. Many would cite reasons like income disparities, low levels of formalisation, lesser organised sector jobs, low agriculture productivity among other things.

The above reasons may be true in parts, but they all assume that the macro-levers can be improved in the short run without systemic, institutional, or human capital reforms. There’s mostly an economic consensus that any nation has to work with. I would call that the natural progression rate of an economy.

The Indian economic slowdown may be the result of larger forces at play within the global economy. After all, we were riding high on the global high tide along with other BRICS. An alternative theory is that emerging markets are struggling with the downside of democracy and the chaos that comes with it. The fact that China is the only shining beacon that had the escape velocity growth after the 1990s, supports this thesis.

The last word

If globalisation and free trade can push poor nations out of poverty, the forces in reverse can create a slowdown as well. While the jury is out analysing reasons for this global phenomenon, I don’t think there is an easy answer to this.

I’m inclined to believe that if we rise the high tide of global growth, we’ll also share the drop when the tide recedes. We grow as the world grows around us. China was an extraordinary effort, so were Asian tigers or the OECD nations. India needs that escape velocity.

Doing that will need us to defy global headwinds and undertake efforts out of the ordinary. Time for a new China on the global stage? The world desperately needs an alternative.

The article first appeared for The Economic Times in March 2023: