Great market returns are likely in India. But you also need an expectation reset

July 24, 2023 - Anurag Singh

Is a 12% CAGR from Nifty50 pessimistic? No, it’s not. Market valuations in India are already stretched, and new wealth creators are needed to beat the benchmarks consistently. Excess liquidity and record high fund flows will only make markets more expensive, thereby moderating future returns.

Till now, we have discussed the golden era of the stock market and whether India can surpass China’s economic growth.

In this third article from the series explaining the Indian stock market returns and way forward, we will address the key question that was left open in the first one — why will the market reflect a moderate 12% returns for this decade versus the much higher benchmarks we have seen in previous decades? Why such pessimism, you may ask.

For the record, it is not pessimism at all. A 12% return on index (Nifty) would still count as one of the best returns globally for major markets. Let me try to make a case for it and call out the assumptions that can change this, both on the upside and downside.

Easy pickings gone: where are the new wealth creators?

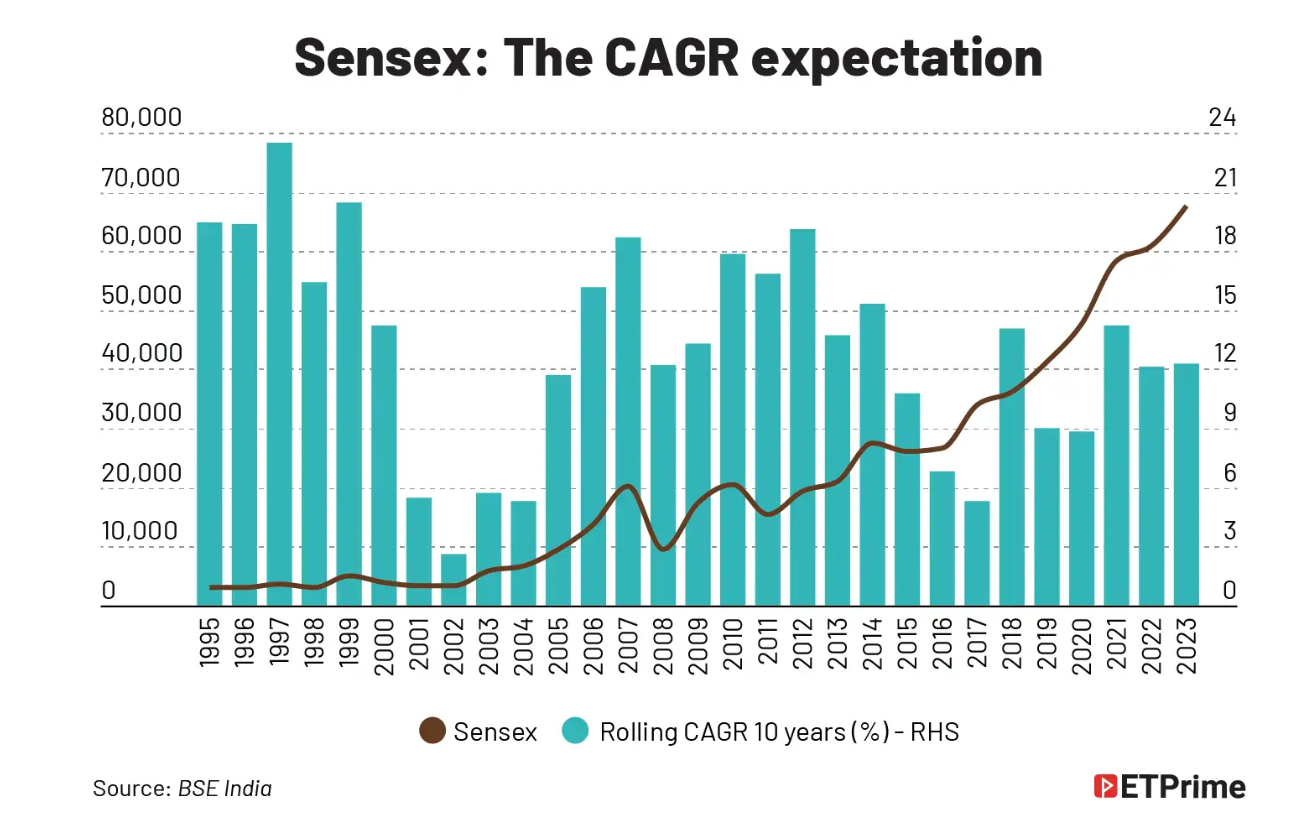

In my first article, the emphasis was to understand historical market returns through the lens of development in the Indian economy and easy pickings that liberalisation brought about in the markets. Since equity was not a mass culture in the 1980s, most quantum returns in the segment were made in the early phases. The 10-year CAGR on Sensex or Nifty point to the diminishing decadal returns since inception.

This is very intuitive as most returns are captured in early stages of any asset growth. The last decade (2011 to 2021) yielded a very humble 11% on Nifty Total Returns Index (TRI). Adjusted for dollar, it was a modest 8%.

The previous decade also saw the lowest number of new wealth creators getting listed or gaining a large-cap status. Outside of Bajaj Finance and Avenue Supermart (DMart), it is hard to recall any new player getting into the big league. What does this indicate?

The market is maturing faster than we expect and new opportunities are getting limited. To be fair, there are new listings, but they are coming to the market to provide exit to current investors rather than any particular need for fresh capital. What’s worse, most of these IPO players are in the business for more than 10 years and have already saturated markets. I wouldn’t call such listings as IPOs anymore.

Look at the listings in the life insurance space that came in with much fanfare in mid-2015 or later. With all the talk of ‘under-insured’ Indian market, many failed to see the fact that these private companies have existed for 15-plus years already. Where have the stocks gone since listing? Nowhere!

Which new bank listed in the last decade has created significant wealth? Any consumer discretionary or auto company comes to mind? As for the other ‘New Age’ digital platform companies’ IPOs, the less said is better.

When a market doesn’t create new wealth generators of the 1990s and 2000s, how do you expect the returns to fly higher than average? You see how the 12% Nifty returns also begins to look more ambitious now. Can something change the trajectory here? The GDP growth, probably.

GDP growth: can markets grow outside of the economy?

In my second article, I emphasised on the GDP growth phases for global economic powers and what history can teach us about economic growth rates. We analysed how sustaining 8%-plus growth rates for more than a decade is quite challenging and very few countries have been able to do this in history.

After World War II, global growth was mostly driven by the majority of OECD nations that grew to prosperity within a couple of decades. In the 1970s to 1990s, the Asian tigers did the same and got rich with investments in human capital and maintaining macro stability. Overall, global growth, however, was slowing down from 5.25% in the 1970s to a mere 3% in the 1990s.

This implied that most rich nations had attained entitled growth and were moving towards a more mature growth rate. The hope was that some new growth tigers would emerge, like BRICS. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa were touted to be the next global growth engines.

After a brief initial promise in 2002-2010, Brazil, Russia and South Africa got stuck in the “middle income trap” of USD10,000 per capita. The GDP growth rates for these nations actually fell to sub-3% or even negative at times in the last decade. These nations clearly lacked what the Asian tigers, Japan or most OECD nations had. But there was one exception.

In the last decade, China defined how it was possible for a nation of that size to become a middle-income country by sustaining near double-digit growth for two decades. Time would tell if it can break the “middle-income trap” that no nation has done since the 1990s. But it leaves a lesson for us. Growing at 8%-plus for two decades is not natural progression and needs extraordinary efforts, comparable to those of China. Done well, it can work like magic. But accounting for the cost of democracy in India, is even 6% plausible for this decade?

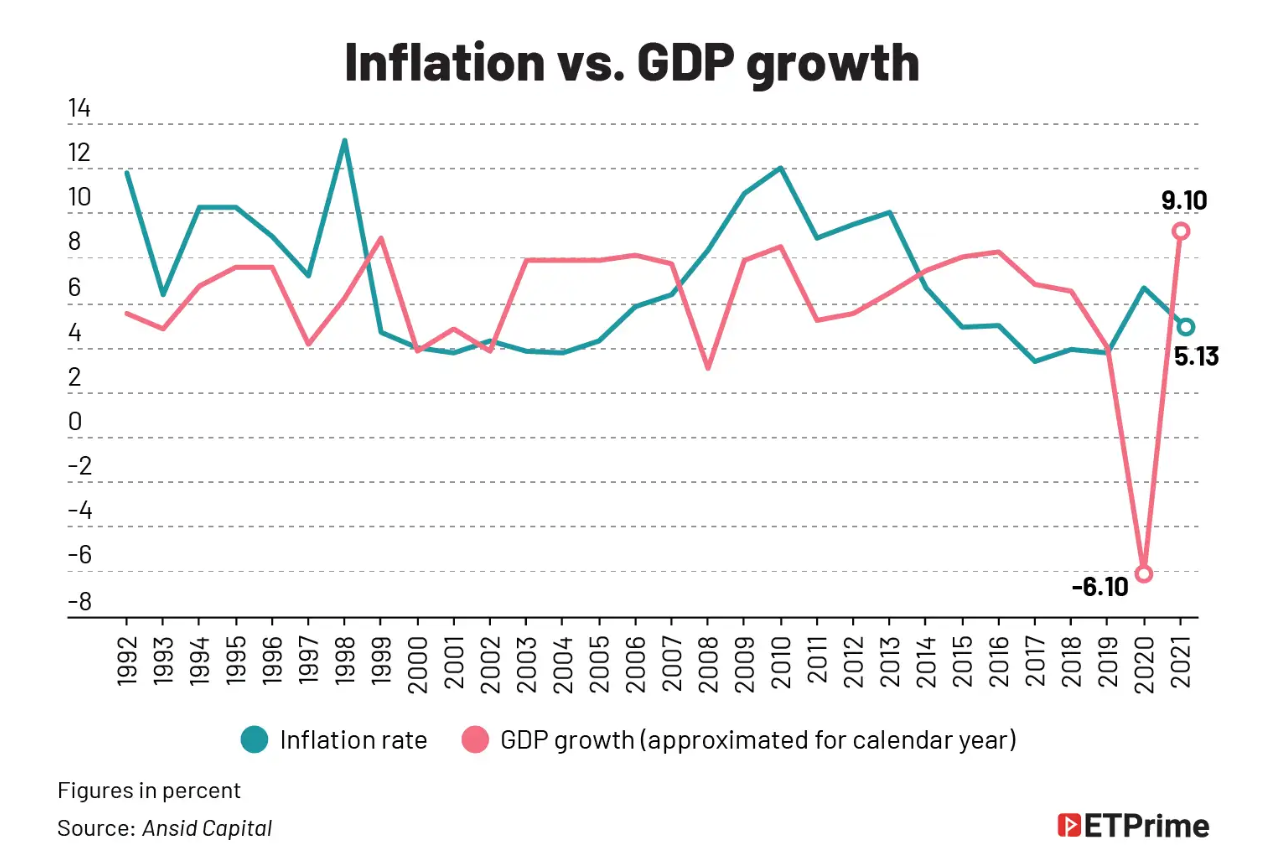

Recall that global growth was mere 2.7% for the last decade and is projected to be below 2% for the current one. It is looking increasingly tough for any major economy like India to grow above 5%. It’s not that I base this on global statistics. Look at how investment-to-GDP has peaked out for India in 2008 and is below 30% now since 2015.

Bank loans to industry peaked at 22% of GDP in 2014 and is on a steady drop to below 14% now. Let’s assume a 6% GDP growth for India in the best case, that will still shave off some returns from the markets, 2% to 3% to be precise compared to the 11% we got between 2011 and 2021. The 12% return path now looks even more challenging as you can see. But there is a twist that can help us in a way — inflation.

Inflation: a savior or a giant slayer?

We often forget that markets are about nominal growth. All-time highs after a few years are a bit less as inflation catches up fast in developing economies. But inflation is good for markets in the short term as profits increase, margins expand (if price rise keeps ahead of costs), ROEs look better. In a 7% inflation economy, companies can always expect to deliver double-digit sales growth just at the back of rising prices.

The 20% CAGR for Nifty between 2001 and 2011 was at the back of 7% inflation. Add to this a GDP CAGR of 7% and we get an easy 14% CAGR for the markets. What explains the rest 6% to get to 20% for the decade? Well, that comes due to the new wealth creators in the economy.

Recall TCS, Infosys, HDFC twins, ICICI Bank, Maruti, Asian Paints, etc. To start with, the valuation base was so low that the Nifty grew by 72% in 2003 itself. Compare this to the decade from 2011 to 2021, Nifty returned a CAGR of 11% on the base of 6% inflation and 5.6% GDP average. Barely anything was contributed by the equity risk as most new listings did poorly.

Current decade may have inflation contained at 6% (depends on how the global economy plays out) and with GDP of 6% added, a reasonable 12% CAGR is the most likely scenario for Indian equities. You don’t wish for higher inflation as it may hurt the economy. We can wish for higher GDP growth but that is unlikely in absence of efforts out of the ordinary.

Is 12% CAGR pessimistic or optimistic?

So, where did we start in this decade? Nifty was a good ~17,800 (22x multiples) by the beginning of 2022 and is at 19,800 now — there are noises of markets being too frothy. If RBI contains inflation at 6% and the economy grows at the best projected rates of 6% or thereabouts, the 12% equation looks fine.

However, we entered this decade with very high valuations. Outside of existing giants, we need some new wealth creators that can beat market returns on a consistent basis. Else, there is always this downside risk. Any recession coupled with low inflation can bring the decade to below 10% — hardly the return you expect from a growth market.

By now, you can appreciate that 12% CAGR from Nifty is a very optimistic estimate. These are not bad returns but don’t exceed expectations of most investors. Excess liquidity and record high fund flows will only make markets more expensive, thereby moderating the future returns.

Remember, fund flows don’t increase earnings, they only make current stocks more expensive. Just like more money chasing the same goods creates inflation. Making money is rarely a formula but that’s what the current proponents of SIPs are making it look like. Let’s leave that for another discussion.

The article first appeared for The Economic Times in July 2023.